The Prouty Plow: A Symbol of Hanover

The Prouty Plow: A Symbol of Hanover

David Prouty 1778-1846

David Prouty was born in Scituate on May 18th, 1778. He married Lydia Stoddard in 1795, and the couple had five children: Margaret, Lorenzo, Lydia, Veniah, and David, Jr. Prouty moved his family to Hanover in 1811 where they lived in the 18th century house built by Thomas Hatch, and still standing today at 1041 Main Street in North Hanover. Prouty had “feeble health,” but he opened a store, ran a cotton cloth weaving business, attempted a shoe making business, and farmed.

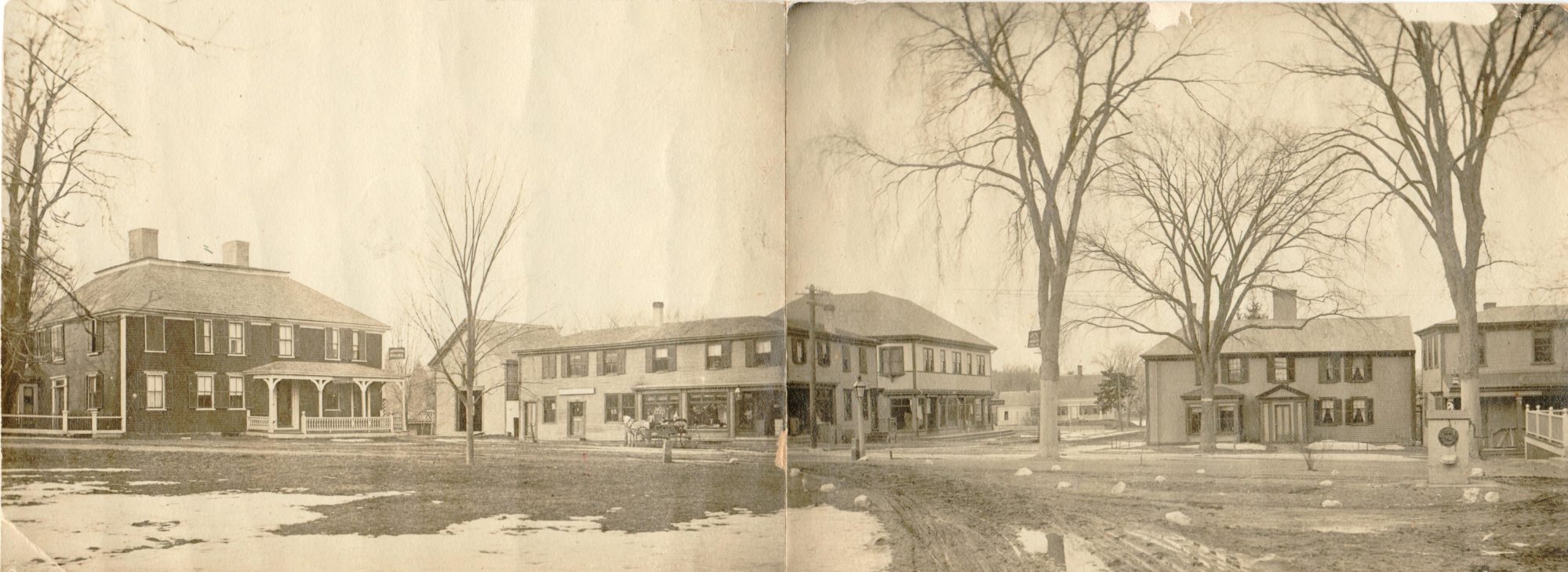

By the 1830s, Prouty began experimenting with plows made from cast iron. Elias Phinney described how Prouty was “a practical farmer” but had a “philosophical mind.” His plow and his business were both very successful. He formed a business partnership with John Mears (1795-1879) and gradually moved his company to Boston beginning in 1833. Prouty moved his family to Dorchester by 1837, to be closer to the Prouty & Mears warehouse on North Market Street next to Quincy Market. Prouty’s son Lorenzo (1806-1872) joined the business and married John Mears’s daughter Lucy (1818-1899). Lorenzo Prouty continued the business as the David Prouty & Co. into the 1850s.

David Prouty died on March 31st, 1846, at the age of 68. He was buried in the Dorchester North Burying Ground in Tomb 373, where fourteen other members of his and his partner Mears’s families were interred, including his wife and several of children.

Prouty Plow a Success

"Deacon John Brooks of Hanover well recollects when the first plough made by Mr. P. was put in operation. It was taken to a gravel-knoll, on the highway, near the present residence of Mr. Samuel Brooks, Main street, and many were the prophecies that, as soon as the oxen were attached and an attempt was made to break lip the almost impenetrable surface, it would at once be shattered and found worthless. But Mr. P., who had all confidence in his success, held the plough himself, guided its operations, and, as the team moved on and the furrows were turned, the prophecies of failure vanished as the dew before the morning sun."

The Prouty Plow won many awards and premiums at agricultural fairs from the Massachusetts Agricultural Association, Mechanics’ Charitable Association, Maryland State Agricultural Association, and many others including the Czar of Russia. A Prouty Plow was displayed at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851. The Prouty Plow was also used in plowing races put on by local agricultural societies. Typical results from the Essex Agricultural Society’s report for 1843 performed well with results for a plowman and driver averaging about 20 7-inch deep, straight furrows in 40 minutes on one-sixth of an acre.

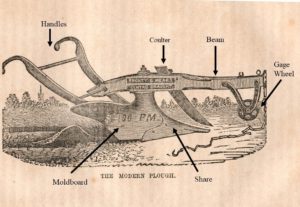

New England’s farmers used a plow with a wooden moldboard shod with iron which needed constant repair in the rocky soil. New Englanders and other American farmers were skeptical of anyone who tried to create an iron plow, they thought “the cast iron poisoned the land, impaired the fertility and promoted the growth of weeds.” People like Thomas Jefferson and Daniel Webster attempted to invent better plows of iron without much success.

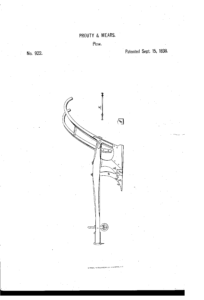

David Pouty was not the inventor of the cast iron plow, but as John S. Barry in A Historical Sketch of the Town of Hanover, Mass., describes it, “he was a pioneer in the business.” Prouty and Mears were granted four patents for developments to their cast iron plows in 1836, 1838, 1841, and 1847. The plow’s separate parts of the share, mouldboard, and other components were strong enough for rocky soil and if damaged, could be easily replaced or repaired. Prouty began demonstrating his plows in the fields of his Hanover neighbors. Demonstrations around the country lead to business success and international acclaim for the quality of the plows.

During these same years, John Deere, a recent transplant to Illinois from Vermont, invented a plow with a steel share which was better for cutting up the soil and “scouring” (when the dirt slides off the plow share and mouldboard) on the prairie of the American Midwest. Prouty and Deere were typical of many other inventors promoting agricultural improvements in Antebellum American.